|

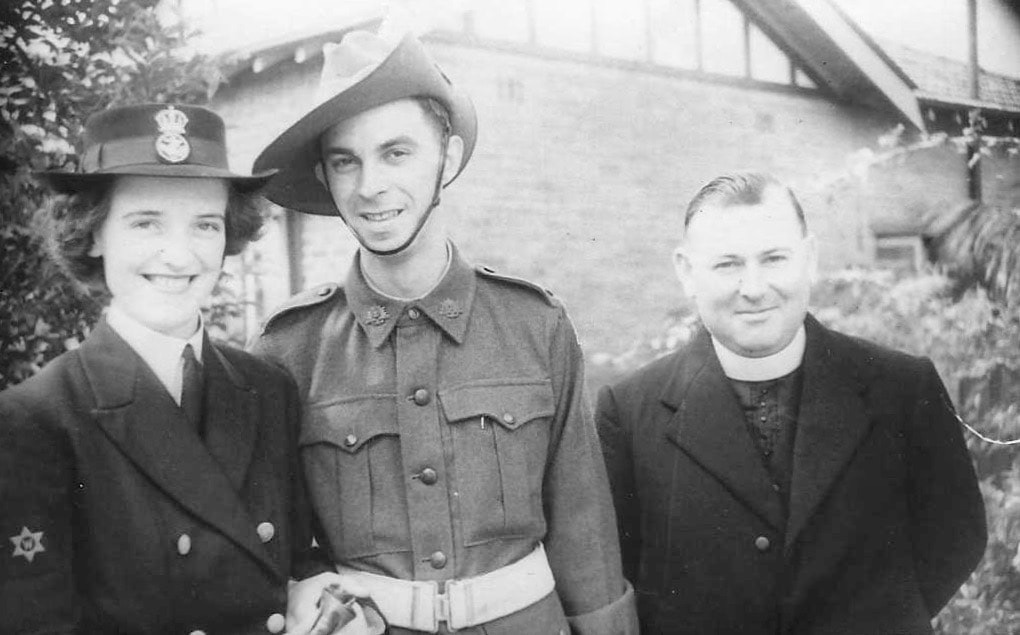

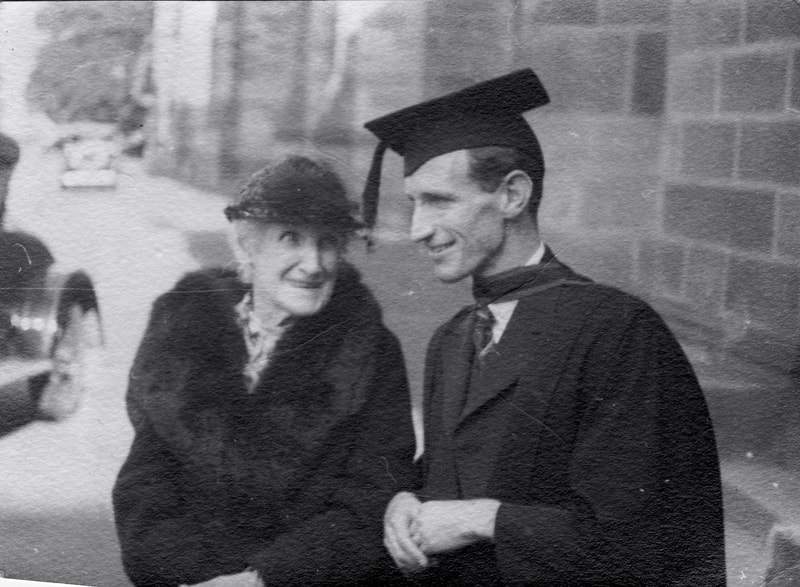

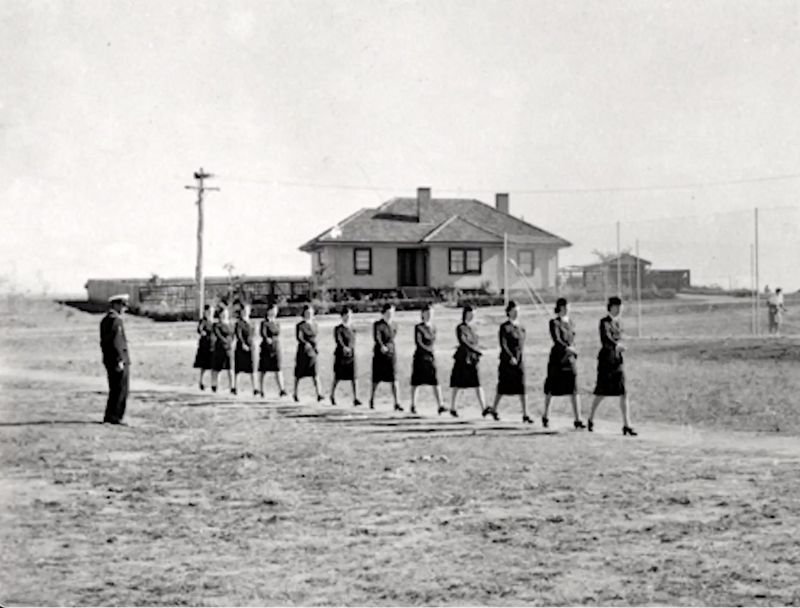

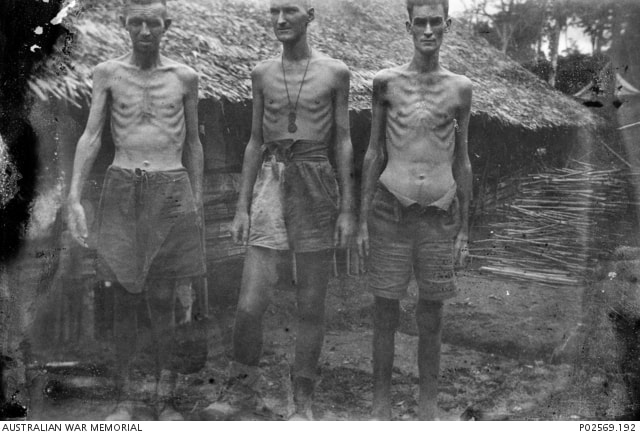

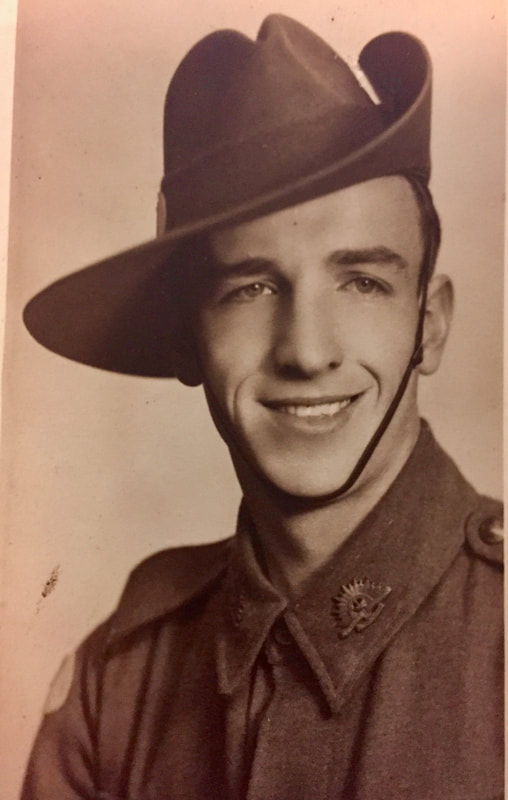

Judith Follett (1921-2005) was one of a little known band of pioneering women who served in naval intelligence in Australia during World War Two. Her role with the Women's Royal Australian Naval Service was secret and unrecognised, and her story has never been told. Judith Geraldine Anne Lusby was born at Cooma in the Snowy Mountains of New South Wales, in 1921. Her mother Caroline Lusby (née Fitzhenry) had come from the northern rivers district of NSW, where her formidable grandmother had founded hospitals at Casino and Ballina. Judith's father was John Lusby - a school principal and classics master. As an itinerant young teacher, he had humped his swag from job to job in the "stifling noons" outback. Menindi to Broken Hill was "70 miles with one pub", he noted in a 1908 letter home, which quoted Lawson's lines: "the water warmed in the bag that hung to his aching arm like lead." When John met Caroline it was love at first sight ("and all sights after"). Marriage quickly followed. The family continued to regularly relocate by train to various bush towns. Judith's eldest brothers John (known as "Jack”) and Maurice ("Moss”) were born in Sydney, while elder sister Gwenyth was born at Taree, brother Robert ("Bob”) at Balranald and younger sister Elizabeth at Kempsey. Judith's abiding memory of childhood was the poverty of the Great Depression. "There was no stigma about being poor, because everyone was poor”, she recalled in 2001. "But, a wonderful thing about our parents was that none of us stopped school to go to work. We lived poor so that everyone could go to school and university if they wanted to. I think the great ambition was to see us all well educated, and that, to my mind, was a wonderful thing that they did for us.” A bright student, Judith was accepted at the selective Sydney Girls' High School. She was artistic, vivacious, and a great story teller. Creativity and theatricality were in the genes - Errol Flynn was a cousin of the northern rivers branch of the family. Her teenage poems, letters and short stories often found their way into the Sydney newspapers, tracking her childhood dreams of "a life on the ocean, a literary career and success as a ballerina”. Elder sister Gwen had blazed a trail studying medicine at university, graduating in 1939 among the early women doctors to pass through the University. Judith followed Gwen into Sancta Sophia, the Catholic women's college at Sydney University, where she studied for a Bachelor of Arts. As her student days drew to a close, she found herself pondering a variety of careers, including a job suggested by her scientist brother Maurice Lusby as assistant to a professor at the CSIR. Maurice was an engineer, and radio pioneer, whose room at the family home resembled a science fiction laboratory. He built a crystal wireless set and was a ham radio broadcaster. He would shout to his siblings to come and listen to voices from around the world "Russia, Timbuktu, Chile!” Here, Judith and her siblings were trained in the art of radio broadcasting and receiving. At the outbreak of War, Judith was in her final year of school. Eldest brother Jack Lusby, a well known cartoonist and writer for The Bulletin, had been an amateur pilot before the war and joined the airforce. He flew with the famous Squadron No. 3 in North Africa, and later returned to work as a test pilot (“he wasn’t looking for safe jobs”, remarked Gwen). Brother Maurice was blocked from enlisting in the airforce by the Manpower Provisions and was sent instead to the Radio Physics Laboratory at Sydney University, where he worked on the development of radar. Maurice then sailed for Washington as Australia’s Scientific Research Liaison Officer. The Pacific war broke out during the voyage. He then criss-crossed the United States and Canada, gathering information on radar and other top secret scientific developments and despatching equipment to Australia. At Princeton he encountered Einstein playing hopscotch on the footpath. In May 1943, he transferred to London by Atlantic convoy and faced the Blitz, before returning a year later to Washington, where he gathered a team of MIT scientists to return to Australia to work on beach landing radar. Youngest brother Bob also sought enlistment in the airforce but was rejected on account of colourblindness. Bob and Judith had been inseparable as youngsters, climbing rocks and tearing around in billycarts. It was Bob who introduced Judith to her future husband, Aubrey Follett from Bungendore. Bob and Aubrey worked together at Hawkesbury Agricultural College and became great friends. After being rejected from the airforce, they went down together to enlist in the Army. Bob's fate turned on his knowledge of morse code and Maurice's radio equipment, which had him immediately accepted as a Signaller assigned to the 2/30th Battalion of 8th Division. The 2/30th were sent to Malaya, and became the first Australian battalion to meet the Japanese in battle during the Second World War. Bob and his comrades were then captured in the Fall of Singapore. Aubrey was meanwhile sent to the Middle East and later New Guinea where he served as a Staff Sergeant and was mentioned in despatches. With Bob vanishing at Singapore, Aubrey and Judith's relationship blossomed and they were married in 1944. By that time, Judith and her sister Gwen were also serving the war effort. Gwen had volunteered to serve as an army doctor at the outbreak of War, but was not accepted until 1942, by which point the threat of imminent Japanese invasion had forced authorities to accept women into formerly male-only roles. Enlisted in the Australian Army Medical Corps (AAMC) and posted to the 113th Australian General Hospital at Concord, Gwen served as a Captain and later Major commanding the medical division there, treating Allied and enemy servicemen, including Japanese POWs whom she insisted should receive equal medical care, even as her own brother Bob worked as a prisoner of the Japanese. Only around 26 women doctors served in the Australian Army Medical Corps during the War. Only five attained the rank of Major. The men called her “sir”. In June 1942, The Catholic Weekly reported on its social pages that third year Sancta Sophia arts student Judith Lusby had celebrated her 21st birthday party by entertaining a number of military, airforce and university friends at the home of her parents in Roseville. Her sister, Captain Gwen Lusby AAMC was there, while her three brothers were overseas: "John is a fighter pilot, Bobby in the AIF is swallowed in the Singapore silence, and Maurice, recently arrived at Washington DC is scientific research officer attached to the Australian Legation. Younger sister Elizabeth is a resident student at Santa Sabina”. The women of the WRANS were not yet formally "enlisted” in the services, but the paper noted already that Judith was "doing a war time job for the duration for the Commonwealth Government”. A week after Judith's birthday party, Japanese midget submarines entered Sydney Harbour and torpedoed the HMAS Kuttabul. In a 2001 interview, Judith remembered being in Sydney for the attack and hearing the sirens blare: "When I got back to Harman, my section were busily identifying those midget subs. They only sent messages to the mother sub outside Sydney Harbour at midnight. We used to sit there like vultures waiting for their messages." "Harman" was the navy's communications base in Canberra. A small group of women had been assisting at Harman since April 1941, but the formal foundation of the Women's Royal Australian Naval Service (WRANS) came on 1 October 1942, when they were sworn in as enlisted personnel. Judith was formally enlisted as an Assistant Writer on 30 November 1942. She and her fellow WRANS were to perform vital intelligence work for the war effort, though the story is little known. In a 2008 history thesis on the development of Australia’s naval signals intelligence, Joseph Streczek wrote: "During the war years it was the WRANS who were the backbone of the RAN’s signals intelligence effort, performing a wide range of duties such as interception, RFP and direction finding operations, punch card machine operations, encyphering, administrative tasks and the many minor jobs which keep such an organisation functioning. Without the WRANS the RAN contribution to the signals intelligence effort against Japan might have been much less valuable. Sadly theirs was an invisible contribution and one which they could not discuss nor for which they could receive public recognition." Even Judith’s family knew little of the nature of her wartime work: "Mum served in the Navy at HMAS Harman, between Canberra and Queanbeyan,” her daughter Rosemary Follett recalled in 2012. “She was in naval intelligence in some fashion that, till her death, she didn't discuss in any detail - she took it very seriously. The only detail that I was vaguely aware of was that she did at times know of the movements of Japanese submarines and also any troop carrier that my father was on at the time.” Judith did share stories with her daughters of the lighter side of naval service, such as the occasion a senior officer mistook her notes on the knitting stitch pattern k1,p1,k1,s1,psso for a secret code. She was a contributor to the base newsletter Harmania, and in between lively accounts of dances, sporting matches and “off watch” romances recorded in its social columns, Judith is noted as the ballet mistress leading afternoon classes for some two dozen WRANS in the camp Recreation Hall. Elsewhere she contributes a poem entitled “P.O.W.”, expressing something of the grief left by the silence of Singapore: “Scarce nourished by alien rice, My son, you toil with hallowed hands, You are the living sacrifice.” In 2001, Judith gave a rare account of her naval service for a family history: “I went to university for three years, and then went straight into the navy. I worked in naval intelligence. Five graduates, four of whom were my friends, were chosen by this Lieutenant Moriarty who came to our college, Sancta Sophia, and asked if we would go to do some secret work in the navy. “The cause of all this was that my brother Maurice was in Washington and he was well aware of the kind of work the navy wanted us for - and he said to somebody 'my sister could do that'. And so, I suppose that was how the navy heard of me. "We came down to Harman and there was a gentleman from Mi5, who came from London to instruct us. And he said we were never to explain our work to a living soul, otherwise we'd be shot. And I remember him saying in his English voice: 'Rather messy but still, I've shot so many'!! “As far as I know, that work has never been described. On TV they explain about the Enigma code they got from the Germans - but never has anybody explained the work we did. Roughly I can tell you that it was a method of identifying ships, airplanes, and submarines from the way they sent their morse code. "We could recognise somebody sending a message by morse code and we'd say 'That's that sub near Saigon!'. We got to know them and used to measure them and photograph their dots and dashes on a primitive TV screen. “I think that's about all I can tell you. “I was in charge of this group. We worked in a little shed with soldiers marching around for our security. I remember seeing the bayonets pass by the window, and we had to have a password to get through the gate towards this little hut. But it was a great time - we had a lot of fun. We didn't get paid much, but we had a lot of fun.” The above mentioned “Moriarty” was Lieutenant Oliver Morrogh Moriarty RANVR, who had been stationed from February 1942 at the RDF radar school at the RAN’s Rushcutter training facility, and was transferred to Harman in November as Assistant to the Officer in Charge. His work on radar would have brought him in contact with Judith’s brother Maurice, and this probably explains her recruitment. Moriarty also visited Washington in March 1944 recruiting for RAN signals intelligence, not long before Maurice returned to Australia with a team of MIT radar scientists. Judith advanced to Leading Writer in June 1943 and Petty Officer Writer in January 1944. A newspaper clipping from that year reveals something of the frenetic pace of love in wartime. Petty Officer Judy Lusby married Staff Sergeant Aubrey Follett with just three days’ notice to her parents. The couple had received leave at the same time and "decided that it was the perfect opportunity for matrimony”. A family portrait of the wedding day nevertheless records a fine turnout of Lusby relations for the occasion, though the Anglican Follett family disapproved of their son marrying a Catholic and did not attend. Judith remained strong in her Catholic faith throughout her life, eventually converting her formerly reluctant husband to the Roman rite. After the wedding, Aubrey was back to the fighting in New Guinea. Also absent from the wedding party was Judith's brother Bob, still missing in the Singapore silence. A year later, in May 1943, her mother Caroline wrote to The Sydney Morning Herald begging the authorities for news of the missing men. "15 months can seem like an eternity to imprisoned men. I strongly urge and plead that something be done to break down all obstacles and open up communications with our boys.” At that very time, Bob and his comrades were commencing work on the Thai-Burma "Railway of Death”. After a time at Changi, Bob had been assigned to F-Force - the worst hit of all the groups working on the line - and presumably sent to Shimo Songkurai, a camp so hellish and thick with malaria, dysentery and cholera, that within a month just 200 of the 2000 men in the camp were considered fit for work. To discourage sickness, the Japanese bashed the ill and reduced their rations. Men were carried on stretchers to the railway to sit and swing a hammer. When reminded of the Geneva Convention, Camp Commandant Fukuda would shrug his shoulders and say, “Geneva is a long way away.” While the family anxiously awaited news of Bob, Judith's brother Maurice eventually brought consoling news that the war would soon be over. "Mark Oliphant had once told me about this thing called an A-bomb which was about the size of a pound of butter and could knock out a city”, Maurice recalled in 1995. "When I left London, I was given a message from Admiralty there on the date and target of the first A-bomb to land in Japan. I took it to the First Naval Member at Victoria Barracks, Melbourne Headquarters. I knew what the message meant.” When the Japanese finally surrendered in August 1945, Australian POWs began returning home through the army hospital at Concord, where Judith’s sister Gwen was serving: "Although they looked shocking because of the awful conditions under which they worked on the Burma Railway - they didn’t actually talk about their deprivations,” Gwen recalled in 2001. “But they looked very thin - ribs sticking out and so on - and had all the evidence of scurvy and beri beri and lack of vitamins. Every time a group of prisoners came in I would be extra anxious because I would be looking for Bob — but of course, I didn’t see him.” Judith's "hero” brother Bob had succumbed to berri berri, dysentery and cerebral malaria at the squalid Tanbaya hospital camp in Burma on 20 September 1943. News of Bob's death did not reach his family until after the war. "I was at Rushcutters Bay in the navy. They called me to say that a telegram had come but they wouldn't give it to Mum, who was very upset, so could I come home,” Judith recalled in 2001. "I went to my commanding officer and asked for permission to go home. He must have rung army records, because he came back, put his arm on my shoulder and said 'The captain's car is at the front to take you home'. So I went home in this great naval car with the ribbon flying at the front. The naval driver said 'Bad news love?' I said I've no idea, but they wouldn't give the telegram to my mother. And he said 'Bad news'. They were dreadful times. Terrible times.” Judith completed her service with the Navy in October 1945. The Folletts had three daughters in quick succession and moved to Canberra where Aubrey found work as a Hansard reporter in 1952. With the government job came a government house - a duplex at Yarralumla, where the family happily settled after difficult accomodation in Sydney. She later commenced a career teaching at the Catholic high school for girls now known as Merici College. Judith joined 27 nuns as the only lay person on staff. She taught English, Latin and French. The library at Merici College is now named the "Judith Follett Information Centre” in memory of her pioneering work and long service to the school. Though the ratio of religious to lay staff in Catholic schools has now been completely reversed, Judith’s teaching career at the college was truly groundbreaking in those times. Nuns worked for free and had to be persuaded of the need to offer Judith a wage for her labour. In Canberra, Judith continued to write short stories, painted and became a pioneer member of the Potters Society. Her letters to the papers record her pride in the city, and interest in the politics of the day. Despite, or perhaps because of the trailblazing ways of the women in her family, the advent of female quotas left her unimpressed: "What serious person, male or female, seeking a political career would care to proceed to office on the basis of a mechanical quota system...”, she wrote to The Canberra Times in 1994. "Women don't need this patronising gallantry. I therefore challenge the women of Australia, if they want to become worthwhile politicians, professors or priests, to stand on their own feet and rely upon their native grit and determination. What's wrong with equal opportunities for all?” Judith took great pride in the achievements of her daughters, especially when her second eldest Rosemary became Chief Minister of the ACT: "We were a fairly conservative family and could never work out how we managed to rear such a radical daughter,” Judith recalled in 2001. "She used to have great debates with her father from quite an early age, and as soon as she could, she joined the Labor Party and worked her way up ... and when ACT government came into being, she was voted into the job of Chief Minister - and actually was the first woman in Australia to head a government - ahead of Joan Kirner in Victoria and Carmen Lawrence in Western Australia. She held that position in 1989 when self government came and she held it with great distinction.” Interviewed by Nikki Henningham for the Women and Leadership oral history project in 2012, Rosemary Follett said that her mother and aunts had provided great role models for her in life: "My mother raised the family, she had three daughters. But when we came back to Canberra, she really did rebel in a way, in that she was quite determined to go on with her university studies. She enrolled in a Masters at what was then the ANU College. She was there with A.D. Hope, the poet, whom she idolised, and then she became a teacher, the first lay teacher in Canberra. “So I come from pioneering women stock! "My mother was a teacher of literature and an incredibly well read and well educated woman, my father too was very well read... so we really did have that intellectual stimulation. “I admired my mother and my aunt Gwen Fleming, who kept practising as a doctor almost up until she died aged 95. And my remaining aunt Elizabeth Lusby, who is a nun, she was the prioress of a famous Catholic boarding school, so she was a high achiever as well... So I guess there were those models, all the time.” Youngest daughter Elizabeth Shaw (Libby) remembers Judith's later years in Canberra: "When Mum retired from teaching she took up pottery. We all still have some of her pieces. Dad also eventually joined her in this craft and together they turned out many lovely functional pots. I remember almost the entire garage at Garran being turned into The Pottery, complete with potting wheel, drying shelves, glazes and kiln. Mum also built, with Dad's help, her own wood fired kiln in the back garden. This had mixed results, mainly small explosions and much disappointment. Mum was always a great reader, thinker and crossword solver! She was totally engaged with the world and everyone around her.” Aubrey Follett passed away in 1979, leaving Judith to a long solo retirement in Canberra, where she died in 2005. Despite a long decline in physical mobility, Judith remained intellectually agile and engaging until the end. She took obvious pride in having been one of the women pioneers of the Royal Australian Navy, and in belonging to a family that had answered the call to service during Australia's darkest hour of need in World War Two. If her contribution was “invisible and unrecognised”, still its ripples of example continue to the current day. Her granddaughter Lieutenant Commander Anna Kane, an operating theatre nurse and naval reservist, served at HMAS Harman while on courses ahead of deployment with the Royal Australian Navy to the Middle East in 2020/21. Of Judith, she simply says: “Grandma was an inspiration to many generations.” Further reading and viewing

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorTheo Clark. Archives

September 2022

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed